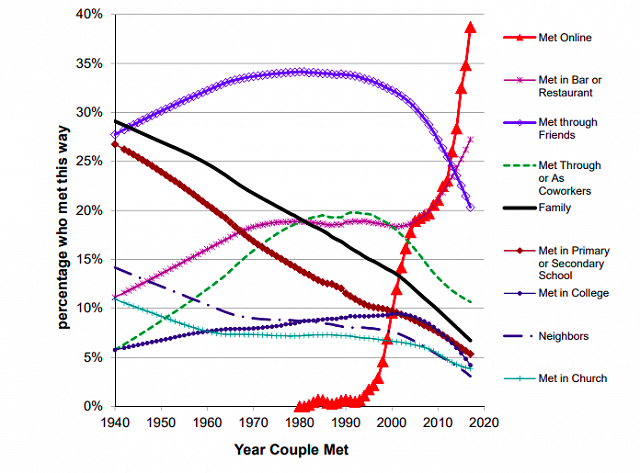

Dating apps are tough on the middle-of-the-road guy. If you are not one of the most desirable men on the app, you probably are not getting much attention. He found that inequality on dating apps is stark, and that it was significantly worse for men. The reason for this gender disparity is probably not that women are more appearance-focused than men. The most likely explanation is that women, who are generally less likely to initiate contact, have a higher threshold when they do so. For many women, though certainly not all, if they are going to break with gender norms, it is only going to be for a really attractive guy. In order to put this dating-app inequality in context, Goldgeier—inspired by an ingenious Medium post about the socioeconomic prospects for men on Tinder—considered how it compared to financial inequality across the world. One of the most common measure of income inequality is the Gini coefficient. A good technical explanation of the Gini can be found here , but the important thing to know is that the Gini is measured on a scale, with zero being a perfectly equal society and 1 being completely unequal. The economy for male likes on Hinge has a Gini of 0. The Gini for females on Hinge is 0. Still, though dating-app inequality may be extreme, the chart below shows it has nothing on the distribution of wealth in America. Our free, fast, and fun briefing on the global economy, delivered every weekday morning.

For Online Daters, Women Peak at 18 While Men Peak at 50, Study Finds. Oy.

The A. Send us a Tip! By Dan Kopf. Published August 15, Thank you for visiting nature. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer. In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript. Millions of people use online dating sites each day, scanning through streams of face images in search of an attractive mate. Face images, like most visual stimuli, undergo processes whereby the current percept is altered by exposure to previous visual input. Recent studies using rapid sequences of faces have found that perception of face identity is biased towards recently seen faces, promoting identity-invariance over time and this has been extended to perceived face attractiveness. In this paper we adapt the rapid sequence task to ask a question about mate selection pertinent in the digital age. We designed a binary task mimicking the selection interface currently popular in online dating websites in which observers typically make binary decisions attractive or unattractive about each face in a sequence of unfamiliar faces. Our findings show that binary attractiveness decisions are not independent: we are more likely to rate a face as attractive when the preceding face was attractive than when it was unattractive. Social dynamics in the contemporary world are rapidly changing in response to online technologies. For many, online profiles on sites such as Facebook and Instagram contribute as much to their social lives as their real-world interactions. This is especially true for dating practices, which have been revolutionized by the internet and translated into huge business with millions of users each day logging on to online dating sites in search of potential mates. In this paper we explored the social phenomenon of online dating using a simple binary task that mimics the procedure used by immensely popular online dating sites such as e-Harmony, OK Cupid, Tinder, etc. Two experiments are described that explore the impact of serial dependence on face attractiveness perception in a simplified, real-world context.The experiments employ a rapid adaptation paradigm that has emerged recently in the perceptual sciences whereby subjects are asked to make quick judgements about a rapid sequence of randomly varying stimuli. This method has been used to show robust inter-trial adaptation in judgements of orientation 1 and numerosity 3 in vision, frequency in audition 4 and perceptual synchrony between audiovisual signals 5 , 6. With regard to face stimuli, it has been reported that face identity shows inter-trial adaptation dependencies 2 , as does face attractiveness 7 , 8 , 9. The observation of rapid sequential dependencies in face perception raises an interesting question about the way we judge the attractiveness of unfamiliar people who post profile pictures on online dating websites. In this context, users make sequential, dichotomous decisions about whether a face is attractive or not based on a brief glimpse of a profile picture. It is not clear whether sequential dependencies are robust enough to occur when attractiveness ratings are simplified to a simple dichotomy of attractive or not, as favoured by many online dating sites. Moreover, previous studies 7 , 8 , 9 have used laboratory stimuli, controlling for low-level visual properties for the purposes of drawing inferences about the visual system. An open question is whether these sequential effects still influence our behaviour when real profile pictures are used without the benefit of low-level control. The current experiments will test this using a simple dichotomous task and will do so with the well-controlled face stimuli typically used in laboratory studies of face perception replaced by non-standardised real-world profile pictures downloaded from the public domain. Our findings show that a binary attractiveness rating of a given face is strongly biased by the face seen immediately prior. In short, if the face you just saw was attractive, you are more likely to judge the current one as attractive and vice versa. A trial started with a face drawn randomly from the set of In an unspeeded binary task participants judged a face as attractive or not see Fig.

These statistics show why it’s so hard to be an average man on dating apps

A General procedure arrows and labels are for illustrative purposes only and were not visible during the experiment. Stimuli depicted are examples of photographs taken of men who consented to have their images reproduced for scientific communication. Horizontal dashed line indicates general attractiveness mean attractiveness score for all faces averaged across all subjects. The dashed horizontal line indicates general attractiveness as in panel B. For each subject, we calculated the mean of the 10 attractiveness judgements for each face and the overall mean attractiveness for the whole set of faces. Faces with mean attractiveness less than the overall mean were categorised as not attractive, or as attractive when exceeding the overall mean. We also calculated the degree of autocorrelation in the random sequences of trials presented in Experiment 1. The group mean data revealed that none of the non-zero lags were significantly different from 0. Following the experiment, the eight subjects in each group selected the 15 most attractive faces from the set of 30 they had not seen during the experiment either Set A or Set B. Thus, each image received an independent attractiveness rating given by the number of times subjects from the other group selected it as attractive. An interesting question is whether all face images were dependent on the attractiveness of the face on the preceding trial or not. Figure 1C illustrates the distribution of the profile pictures as a function of the attractiveness score.

Visual inspection of this figure confirms the notion that the whole distribution and not just a part shifts to the left i. In the experiment, each of the 30 faces was presented 10 times in a random order. However, it is possible that by repeating the faces our participants became familiar with them, raising the possibility that familiarity may modulate the inter-trial attractiveness effect. We tested if there was any effect of familiarity by dividing the trials of the main experiment into 10 consecutive blocks of 30 trials and calculating the attractiveness effect within each block. The results are plotted in Fig. These results imply that increasing familiarity with the stimulus set throughout the experiment did not affect the inter-trial attractiveness effect. Our results show that face attractiveness judgements are strongly influenced by the attractiveness of a preceding face, regardless of whether attractiveness is rated by the same observer or an independent rater. This inter-trial behaviour is intriguing in itself, as it clearly demonstrates the choices of millions of online daters are affected by the most recently seen face. However, it is interesting to know if this behaviour is driven by a low-level perceptual mechanism e. To investigate this we ran a similar experiment randomly interleaving upright with inverted stimuli. By contrast, a bias to repeat responses entrained by the speed of the task or when presented with a difficult-to-rate stimulus should occur regardless of image inversions.

Dude, She’s (Exactly 25 Percent) Out of Your League

An independent sample of 16 undergraduate female students was recruited and the same set of 60 faces used in Experiment 1 was used in Experiment 2 and most procedural details were unchanged. The 60 faces were judged 10 times each in a pseudorandom order. A The distribution of responses across the stimulus set black bars when the stimuli were upright, red bars when the stimuli were inverted. B Results of Experiment 2: the effect of inter-trial orientation. The inter-trial attractiveness effect shown for all four orientation conditions. The two left-hand columns show congruent inter-trial face orientation and the two right-hand columns show incongruent inter-trial orientation. The results of the interleaved orientation experiment are plotted in Fig. We compared consecutive trials where face orientation was congruent both upright or both inverted with consecutive trials where orientation was incongruent upright then inverted, or vice versa. The results of Experiment 2 are consistent with the inter-trial attractiveness effect containing a perceptual component because the effect was dependent on relative orientation between trials while the response task was always the same. However, it is likely the perceptual effect does not explain all the data, as the inter-trial effect was in general greater than zero, suggesting a role for response bias, perhaps driven by the subset of hard-to-classify faces that tended to elicit a repeat of the previous response. Importantly, however, the origin of the effect does not change our conclusion, now demonstrated in two experiments, that binary attractiveness judgements for rapid sequences of faces are reliably influenced by the recent past, whether by the previous stimulus or by the previous response to that stimulus. From an evolutionary perspective, attractiveness is a key social characteristic that determines how approachable or desirable we are. Perceived attractiveness is determined not only by our own attributes but by the attractiveness of people around us 11 , These dynamics, however, need to be revisited because the way we interact with others is changing. Here we have extended work using rapid face sequences 7 , 8 , 9 by adapting the paradigm to simulate the simple dichotomous decisions made increasingly popular in online mate-selection. Our results show that assimilative face effects are both quickly acquired and robust enough that even dichotomous attractiveness decisions are biased towards the previous trial. For people sorting through faces in search of an attractive mate, it is a case of love at second sight: their final choice of desirable mate is likely to be one face too late. Across Experiments 1 and 2 we collected data from 32 female undergraduate students enrolled in third-year Psychology at the University of Sydney NSW, Australia. All aspects of the data collection and analysis were carried out in accordance with guidelines approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of the University of Sydney Project No. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects.The stimuli were 60 online male profile pictures retrieved from rating and match-making website www. Images varied in composition, face size and background cues. Some images showed men dressed in casual clothes, others were in formal wear or work uniforms. Being profile pictures from a dating website we presume they were intended to attract female attention. All images but one were in colour and three also contained an animal one dog, one monkey, one dolphin. Images were divided randomly into two sets of 30 Sets A and B. For Experiment 2 we used the same 60 profile pictures. For 8 participants, Set A stimuli were presented in their canonical orientation upright and Set B stimuli were inverted and for the other 8 participants the order was reversed: Set A inverted and Set B upright. Although some of the face images had pronounced head tilts we did not rotate the faces to horizontally align the eyes as is common in face perception experiments because we wanted to preserve ecological validity and our ability to interpret the results in the context of the real world. This may be reduced the expected size of the classic face inversion effect. Participants completed the experiment in a dimly lit curtained booth. Participant responses were recorded using an Apple wired USB keyboard. It was replaced with a white fixation cross which remained visible until the participant made a binary decision; was the face attractive or unattractive. Participants used the arrow keys to indicate a decision. As soon as a response was recorded, the next trial began immediately. In Experiment 1, participants judged 30 faces each face seen 10 times; trials in total in a random order. In both experiments, to minimise local adaptation and predictability, faces were presented in one of eight screen locations equidistant from the fixation cross by 3. How to cite this article : Taubert, J. Love at second sight: Sequential dependence of facial attractiveness in an on-line dating paradigm. Fischer, J.

Love at second sight: Sequential dependence of facial attractiveness in an on-line dating paradigm

Serial dependence in visual perception. Nat Neurosci 17 5 , —43 Liberman, A. Serial dependence in the perception of faces. Curr Biol 24 21 , —74 Cicchini, G. Compressive mapping of number to space reflects dynamic encoding mechanisms, not static logarithmic transform. Alais, D. Auditory frequency perception adapts rapidly to the immediate past. Atten Percept Psychophys 77 3 , — Article Google Scholar. Rapid recalibration to audiovisual asynchrony. J Neurosci 33, —7 Rapid temporal recalibration is unique to audiovisual stimuli. Exp Brain Res , 53—9 Kondo, A. Sequential effects in face-attractiveness judgment. Perception 41 1 , 43—9 Influence of gender membership on sequential decisions of face attractiveness. Atten Percept Psychophys 75 7 , —52 Pegors, T. Simultaneous perceptual and response biases on sequential face attractiveness judgements. J Exp Psychol Gen 3 , —73 Rossion, B. Picture-plane inversion leads to qualitative changes of face perception. Acta Psychol Amst , —89 Kernis, M. Beautiful friends and ugly strangers Radiation and contrast effects in perception of same-sex pairs. Pers Soc Psychol Bull, 7 4 , —20 Strane, K. Females judged by attractiveness of partner. Percept Mot skills 45, —6 Brainard, D. The psychophysics toolbox.

Gender-specific preference in online dating

Spat Vis 10 4 , —6 Pelli, D. The VideoToolbox software for visual psychophysics: Transforming numbers into movies Spat Vis 10, —42 Download references. You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar. Experiment was designed by all authors. Data collection was performed by J. The data were analyzed by J. T and D. All authors wrote the main manuscript text and prepared the figures. All authors reviewed and approved the manuscript. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4. Reprints and Permissions. Taubert, J. Sci Rep 6 , Download citation. Received : 08 January Accepted : 18 February Published : 17 March Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:. Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article. Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative. Cognitive Research: Principles and Implications By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate. Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily. Skip to main content Thank you for visiting nature. Download PDF. Subjects Human behaviour Social behaviour Social evolution. Abstract Millions of people use online dating sites each day, scanning through streams of face images in search of an attractive mate. Introduction Social dynamics in the contemporary world are rapidly changing in response to online technologies. Figure 1. Full size image. Figure 2. Discussion From an evolutionary perspective, attractiveness is a key social characteristic that determines how approachable or desirable we are. Stimuli The stimuli were 60 online male profile pictures retrieved from rating and match-making website www. Experimental Procedure Participants completed the experiment in a dimly lit curtained booth. Additional Information How to cite this article : Taubert, J. References Fischer, J.

Dude, She’s (Exactly 25 Percent) Out of Your League

Article Google Scholar van der burg, E. Article Google Scholar Kondo, A. Article Google Scholar Pegors, T. Article Google Scholar Rossion, B. Article Google Scholar Kernis, M. Article Google Scholar Strane, K. Article Google Scholar Brainard, D. View author publications. Ethics declarations Competing interests The authors declare no competing financial interests. Rights and permissions This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4. About this article. Cite this article Taubert, J.Copy to clipboard. Comments By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. Publish with us For authors Language editing services Submit manuscript. Search Search articles by subject, keyword or author. Show results from All journals This journal. Advanced search. Close banner Close. Email address Sign up. Get the most important science stories of the day, free in your inbox. Sign up for Nature Briefing. I always recommend looking at data in several different ways, to get a more complete picture of what's really going on - such is the case with the member 'ratings' on dating websites. Let's take a look at some data from a different angle

Women Are Much More Selective And Find 80% Of Men Unattractive On Dating Apps, Per Recent Research

The graphs indicated that men rated year-old women the most attractive, whereas women rated men closer to their own age most attractive. This sparked quite a bit of discussion such as the comments in the cross-posting of the blog on allanalytics. So I decided to look at the ratings data in a different way - this time ignoring age, and just looking at how men and women rate each other in general. I found some histograms on p. Whereas the men of all age groups consistently rated year-old women the most attractive which produced a very lopsided chart , their ratings of all women in general produced a very symmetrical chart. In Rudder's book he even describes it as "close to what's called a symmetric beta distribution - a curve often deployed to model basic unbiased decisions. By comparison, women rated men very poorly. Rudder mentions that women only rate one guy in six as "above average. What causes this huge difference in how men and women rate each other? Is one being more honest than the other? Are they rating based on different criteria perhaps men are rating based on looks, and women are rating based on whether or not they think the men would make a good mate?

Perhaps women are hesitant to rate a man highly, because they know that will trigger okcupid to send that man a message letting them know which woman rated them highly? What other factors are perhaps influencing this data? Robert has worked at SAS for over a quarter century, and his specialty is customizing graphs and maps - adding those little extra touches that help them answer your questions at a glance. Makeup, hair, outfits, lighting, etc Men on dating sites are usually way more apt to be disappointed when meeting a woman in real life as well based on her looks. I do think tho that overall women will be more selective and less likely to be thrilled over an average looking guy. Women are biologically programmed to be more selective than men about who they will mate with. Given the enormous disparity between the number of children a woman can give birth to in her lifetime vs. If a woman looks at any profile, you get a response. That can be quite full-on! You want to feel safe so behave differently than you would normally and only look at a few 'safe' profiles.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():focal(749x0:751x2)/sofia-vergara-joe-Manganiello07172344-2715a3505a8b4cedaf753b8a455f5531.jpg)

Votre commentaire: